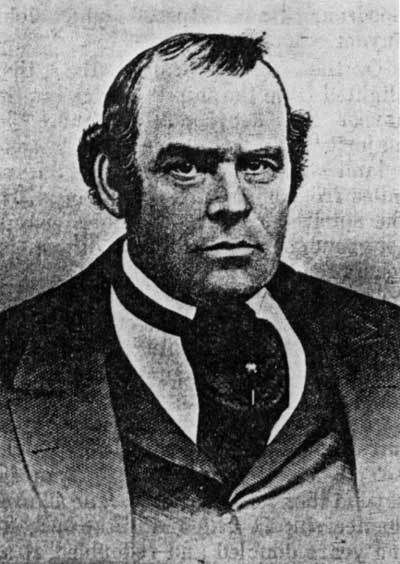

May 13, 1857: The Murder of Parley P. Pratt

151 years ago Parley P. Pratt (12 April 1807 – 13 May 1857) was murdered by the estranged husband of his plural wife Eleanor McLean in a small Arkansas town named Van Buren.[1]

Eleanor McComb (b. 9 Dec. 1817) married Hector McLean in 1841. Soon Hector began drinking heavily, helping to lead to a separation in 1844. Hector promised to reform, and said he desired to seek a religious community to help him overcome his intemperance, and Eleanor moved back in. The couple and their three children moved from New Orleans to San Fransisco looking for a fresh start.

151 years ago Parley P. Pratt (12 April 1807 – 13 May 1857) was murdered by the estranged husband of his plural wife Eleanor McLean in a small Arkansas town named Van Buren.[1]

Eleanor McComb (b. 9 Dec. 1817) married Hector McLean in 1841. Soon Hector began drinking heavily, helping to lead to a separation in 1844. Hector promised to reform, and said he desired to seek a religious community to help him overcome his intemperance, and Eleanor moved back in. The couple and their three children moved from New Orleans to San Fransisco looking for a fresh start.

After attending a Mormon meeting with her husband sometime late in 1851, Eleanor expressed her desire to join the Church, but was forbidden by her husband, who threatened death should she unite with the Mormons. Eleanor continued to attend Mormon meetings, however, and purchased a Mormon hymnal. When Hector discovered her singing from the hymnal he threw it into the fire, beat her, and cast her out of the home, locking the door. Eleanor filed an assault and battery charge, and planned to move to the large Mormon settlement in San Bernadino. The local Branch is said to have persuaded her to stay, and she dropped the charges and returned to Hector, she said, "for the sake of the children."[2]

On May 24, 1854, Eleanor was baptized after Hector finally gave written permission, though he forbade her from singing or reading any Mormon literature in the home.

Parley P. Pratt was assigned preside over the Pacific mission and arrived in San Fransisco July 2, 1854. With little to eat and low funds, the San Fransisco Branch, including Eleanor, cared for Pratt and his wife Elizabeth, who was ill. Parley attempted to reconcile Hector to the Church, but failed. Hector then planned to have his wife committed to an asylum and filed a charge of insanity against her. Parley assigned a young missionary named John Young to help Eleanor.

Young was hired by Hector to do house chores, his identity as a Mormon being concealed. Young helped persuade the directors of the insane asylum against committing Eleanor. When Hector discovered Young was a Mormon he was furious and sent Young away.

Hector locked Eleanor in her room and sent the children to their maternal grandparents home in New Orleans. Soon, Eleanor was able to secure passage to follow her children, and felt her marriage to Hector was over, though it was never legally dissolved.[3]

She stayed with her parents and children in New Orleans for three months, but was unable to convince her father to allow her to take the children so she traveled with a company of emigrating Mormons to Salt Lake City, arriving on September 11, 1855.

Parley had arrived in Salt Lake City from his mission in California on August 18, 1855. He began working at the Endowment House and toured the Territory speaking at various church meetings. He hired Eleanor as school teacher for his children. Eleanor was sealed to Parley on November 14, 1855. It is unclear whether this marriage was viewed as Platonic, meant to ensure Eleanor a worthy eternal companion, or was viewed as other plural marriages wherein Parley resided with many of his 11 other wives. [See the comments below regarding my impressions on the marriage.]

In August of 1856 Parley was called to missionary work in the Eastern States mission and Eleanor asked if she could accompany him to attempt to get her children from her parents home in New Orleans. She told her father she had renounced Mormonism and he allowed her to take the children. On her return trip, however, she wrote her father informing him that she had lied, that she was now "Mrs. Pratt," and that she was taking the children to Utah.

Her father alerted Hector, who was soon in pursuit along with a posse of friends who caught up with Eleanor in Arkansas. Upon learning about Eleanor's illegal marriage Hector had filed questionable charges against Parley regarding the theft of clothing and sent an armed military escort to capture him. Parley evaded them for a time, but in attempting to find Eleanor he was apprehended in Cherokee Nation territory. Upon learning this, Hector set off after Pratt with sword and pistol, Eleanor following in company with the posse.

Parley was taken to jail and bound over on the spurious charges. Hector planned to have Parley arrested again on different charges.

On May 11 Eleanor was brought before a judge and questioned. She testified of her marital difficulties and was released by the judge. Parley was tried on May 12. Hector listed his grievances, but when Parley stood to respond Hector pointed his pistol at him, exciting the trial spectators. The judge postponed the trial until 4pm in order to restore calm. The trial was again postponed until the next morning, May13, at 8 am. According to Eleanor's account, however, postponing the trial was merely intended to stall for time while the judge attempted to convince Hector to drop the matter.As far as the judge was concerned, Parley was innocent and he planned to release him.

Early in the morning the judge delivered Parley's horse to the jail and offered him his pistol. Parley refused and rode away. When Hector discovered the escape he sped off after Parley, following his tracks in the mud left by a light rain. As he approached Parley he fired six shots, hitting his coat and collarbone, but leaving Parley otherwise unscathed. He then rode astride Parley and stabbed him twice in the chest. Hector then rode away, only to return several minutes later to shoot Parley in the neck.

A Mr. Winn, who witnessed the murder which had occurred near his farm 12 miles outside of Van Buren rode for help, believing Parley was dead. When he returned with his neighbors an hour later he found that Parley was still alive and requesting a drink of water. Parley asked if Winn would make sure his belongings be sent to his family and requested his body be taken to Salt Lake City.

Finally, Parley related his dying testimony to the men:

I die a firm believer in the Gospel of Jesus Christ as revealed through the Prophet Joseph Smith, and I wish you to carry this my dying testimony. I know that the Gospel is true and that Joseph Smith was a prophet of the living God, I am dying a martyr to the faith.[4]Parley bled to death from one of the two knife wounds; it had struck his heart. Hector bragged of his deed over some alcohol before escaping across the Arkansas River. When asked if the Mormons would seek to avenge the death of Parley, Eleanor assured them that justice was in the hands of God. Eleanor and a missionary named George Higginson traveled to the Winn farm and helped prepare Parley's body for burial. Higginson buried Parley on May 14, 1857 in Sterman's Graveyard (now called Fine Springs.)

Steven Pratt, a descendant of Parley, explained why circumstances prevented transporting Pratt's body to Utah:

First, the difficulty of transporting a body over the miles of wagon trail led the Saints to bury their dead where they died and move on, which is what they invariably did. Second, the news that Johnston's Army had been sent to Utah precluded taking anything on the trains that did not absolutely have to be taken. Third, during the events of the Utah War there was no real opportunity to recover the body. Fourth, after the Mountain Meadow's Massacre, the people of Van Buren, Arkansas refused to allow Mormons into their region until this century.[5]Subsequent attempts were made[6] until April 2008 when a new archaeological dig was conducted to exhume Parley's remains and transport them to Utah. The remains, however, were not found.[7]

Footnotes:

[1] This much-abbreviated account is based on Steven Pratt, "Eleanor McLean and the Murder of Parley P. Pratt." BYU Studies 15:2, pp. 225-56. For an interesting contemporary newspaper account sympathetic to Hector McLean, see "Tragical," an published May 25, 1857 in the Daily Missouri Republican. The account assures readers of being a "plain narrative of the facts as we received them from the most reliable sources," some inaccuracies are evident, such as listing Parley as having died from a gunshot wound rather than blood loss because of a stabbing.

[2] ibid. 227; Millennial Star 19:432

[3] Pratt, p. 233 footnote 26 reads:

There is no doubt that Eleanor was not divorced from Hector at the time she was sealed to Parley on 14 November 1855. On 1 June 1857 when Hector filed a charge of insanity against his wife in New Orleans, he stated that he wanted her "placed under charge of your petitioner [Hector] as her curator." All through the petition Eleanor was named as his wife. To further substantiate the above, when Eleanor was asked by a reporter of the New York World in 1869 whether she had divorced Hector prior to marrying Parley, she answered: "No, the sectarian priests have no power from God to marry; and as a so-called marriage ceremony performed by them is no marriage at all, no divorce was needed. The priesthood with its powers and privileges, can be found no where upon the face of the earth but in Utah. . . . I regard the laws of Celestial Marriage, or, as the "Gentiles" term it, polygamy, as the keystone of our religion. That is wherein we differ from the sects of the world. They hope for salvation in a heaven where husbands and wives shall be utter strangers to each other; we expect to reach a heaven where we shall rear families, the same as we do here. We could not do this unless we had a revelation authorizing Celestial Marriage; and we could not be saved in the Celestial Kingdom without obeying this revelation. It is the great distinctive feature of our religion, and by it our religion stands or falls" (New York World, 23 November 1869, p.2). Eleanor's explanation of why she joined in a polygamous marriage without going through the formalities of a sectarian divorce from Hector helps the modern reader better understand both the teaching about the authority of the priesthood, and the tenor of the time. For further discussions on the subject, see the following: Wilford Woodruff Journal, 15 August 1847, Church Archives; Orson Pratt, Speech on Marriage, Journal of Discourses, 16:175; Parley P. Pratt, Marriage and Morals in Utah (Liverpool: Orson Pratt, 1856); and Parley P. Pratt, Key to the Science of Theology (Liverpool: F. D. Richards, 1855), chapter 17.

[4]

Pratt, 248.

[5]

ibid. 247.

[6]

In 1902 Samuel Russell, Parley's grandson, corresponded with John Neal, former mayor of Van Buren, and was informed that a Walter Fine knew the location of Parley's grave. Russell wrote to the First Presidency asking what he should do. They recommended that he contact President J. G. Duffin of the Southwestern States Mission and request him to send some Elders to locate the grave "with the view of bringing his remains to this city [Salt Lake] for interment" (Letter from J. F. Smith, John R. Winder, and Anthon H. Lund to Samuel Russell, 19 May 1902, Church Archives). J. G. Duffin visited Van Buren on 3 September 1902 and contacted John Neal, former mayor, John Orme, Justice of the Peace at the time of Parley's murder, and John Steward, the man who drove the wagon that transported Parley's body to the gravesite. Brother Duffin did not visit the grave, but got a promise from John Steward and John Neal that they would assist in the removal of the body if the exact location of the burial place could be determined. They informed Duffin that the Fine brothers could point out the exact location. He was not able to visit them. (James G. Duffin to Anthon H. Lund, 19 December 1902, and Journal History of the Church, 13 May 1857) Further investigation was done in 1912 by Samuel Russell. He visited Van Buren and talked with Thomas Fine, who pointed out what he thought was the location of the grave. After Elder Russell had returned to Salt Lake, he sent a letter to his friend, Calvin Little, of Alma, Arkansas, on 17 November 1912, and asked him to investigate further. Little sent Russell a memorandum giving the location of the graveyard and the approximate location of the grave, which was in the northeast part of the graveyard near a large oak stump--he could not determine the exact location. (Samuel Russell Papers, Church Archives. The Little Memorandum is a letter from A.B. Howell to Calvin Little, dated 11 August 1912. Little must have gotten the memorandum after Russell left, and sent it to him later in the November letter.)Subsequent efforts in 1937 and 1949 are described in Pratt, "Eleanor McLean and the Murder of Parley P. Pratt." BYU Studies 15:2, p. 247, footnote 63. A monument to Pratt was erected in 1951.

[7]

See Robert J. Adams, "Dig at Mormon burial unrewarded," Arkansas Democrat Gazette, April 23, 2008. Interestingly, the article reports the account of a Van Buren resident named Cornelious “Junior” Peters, who "said his great-great-great-grandfather William Stewart gave away the walnut coffin he’d made for himself so Pratt could be buried in it. He wanted to see the coffin and Pratt’s remains." Pratt, however, reports that Parley was buried in a white pine box (see Pratt, 249.) See also Associated Press, "No remains found in dig for Parley P. Pratt," April 24, 2008.

10 comments:

Do you suppose he has been resurrected?

I do not.

;)

of course he was, geeze.. ;)

Sad story, I never knew the details of the murder. Sounds like a soap opera. Eleanor should never have told her father the truth, imo.

And not be to offensive to Parley, but it seemed that he died in more of a lovers triangle quarrel than "a martyr to the faith".

I appreciated the full account. I'd never heard the full background story. I'd also been puzzled by how he could make the dying request to be buried in utah, and now I understand.

Eleanor was much too hasty in writing her father, it seems.

As far as the martyr issue, Parley would not have met Eleanor had he not been serving a mission. He would not have been in Arkansas, either, where he was killed. He died as a result of living the most controversial principle of the gospel in plural marriage.

In regard to lovers triangle, the relationship between Parley and Eleanor was interesting. I see no evidence of what we would style "romantic love" in the letter excerpts, even the private ones, exchanged between Parley and Eleanor. No "I love you," or "my sweet wife [husband]" etc. Though Parley was more affectionate with others, at least this marriage seemed to be more concerned with having Eleanor sealed to a worthy man.

Don: the link in footnote one contains the BYU Studies article from which much of my information was taken.

What a story; I had no idea. It's a bit sad that Parley died for living a principle that so many now consider repugnant.

True. Perhaps it is poor to dishonor our forbears by disrespecting the sacrifices they made.

Post a Comment

All views are welcome when shared respectfully. Use a name or consistent pseudonym rather than "anonymous." Deletions of inflammatory posts will be noted. Thanks for joining the conversation.