Review: Longhurst, "Magnum Opus: The Building of the Schoenstein Organ at the Conference Center of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City"

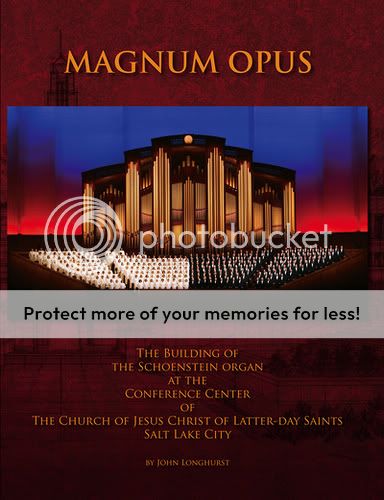

Title: Magnum Opus: The Building of the Schoenstein Organ at the Conference Center of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City

Author: John Longhurst

Publisher: Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Genre: Music Architecture

Year: 2009

Pages: 210

ISBN13: 978–1–60641–199–5

Binding: Hardcover

Price: $32.99

[This review from the Journal of Mormon History vol. 37 no. 1 (Winter 2011): 246-249.]

When Mormon Tabernacle organist John Longhurst saw architectural drawings for the newly proposed Conference Center of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 1996, he was impressed by its sheer enormousness. Naturally, what attracted his attention most was the absence of any sort of visible pipe organ in the original plans. “The rostrum’s rear wall was to be some sort of attractive curtain or grille to be designed later. They called it a ‘screen wall,’” Longhurst recalls (46). Since accompaniment would have to be amplified electronically anyway, given the size of the auditorium, an electronic organ made financial and logistical sense. Still, Longhurst couldn’t hide his disappointment. Admitting his “prejudice” for pipe organs over electric, Longhurst began investigating the possibility of including a pipe with encouragement from LDS Church Architect Leland Gray. The beautiful organ which now serves as the backdrop of the Conference Center rostrum is the result of nearly a decade of consultation, design, and construction previously unmatched in the world of organ making.

Longhurst, who retired as Tabernacle organist in 2007 after 30 years of service, has crafted a biography of the mammoth musical instrument. It contains the detailed analysis of an expert insider written in a style suitable for the interested novice. Recognizing that his readership (and listening audience!) will include many organ aficionados outside of the LDS Church, Longhurst begins the book with a brief description of the Church’s historical geography and structure to the present.

Chapter 2 situates Mormon music in the religious atmosphere of the nineteenth century. From Emma Smith’s 1835 hymnbook (23) to the Tabernacle Choir’s 2003 National Medal of Arts awarded by President George W. Bush (28), Longhurst sees music as a crucial element of Mormon worship, recreation, and public image, a heritage which justified the money, time, and effort it took to make the new organ possible.

Longhurst narrates a history of the organs at Temple Square, as well as some of the key figures in constructing the instruments, in Chapter 3. The story of Joseph Harris Ridges leads off with a harrowing tale of danger at sea. Ridges, a British convert, constructed his first church organ in Australia, an ambition he had formulated as a young boy in London (31).The Saints in Australia wished to make a gift of it to “the Church in Zion,” and presumably paid for its shipping to the Salt Lake Valley. One of the Saints accompanying the organ recorded a terrible storm at sea during which he prayed fervently for protection. The miraculous answer saved the passengers and the precious organ from certain shipwreck (32–33). This organ was set up in the “Old Tabernacle,” a large frame building which preceded the now-famous turtle shell-domed Tabernacle. Pieces of this original organ were incorporated into the (new) Tabernacle’s organ between 1865-1875 (15, 35-36), which was expanded again in 1885.

“Few organs, anywhere, are as well known and highly regarded,” writes Longhurst, listing its technical dimensions with the specificity of an expert lover of organs (36). He also describes the construction and make of organs at the Assembly Hall and the Joseph Smith Memorial Building, accompanied by color photographs. However, the Conference Center organ would surpass all of the others in terms of logistical difficulties and pioneering effort.

When President Gordon B. Hinckley announced plans to build a new and much larger meeting place for the Saints on April 7, 1996, Longhurst played the session’s postlude, his mind filled with the new organ: “I was trying to visualize in my mind a room the size he described. If general conference were to be held there, surely an organ would be needed, but what would that organ be? . . . How were the Tabernacle organists and the rest of the Choir staff to become involved in decisions regarding not only an organ, but configuration of the choir loft and other music-related issues?” (43).

Several days later he found himself looking at the organ-less plans for the new center and went to work to discover the feasibility of a pipe organ for such a large auditorium. “Certainly no organ builder would want to risk tarnishing his reputation by attempting to install an instrument in an impossible situation” (46). Here the reader is introduced to the consultants, considerations, and culture of the organ-building world with its architects, acousticians, and stage designers (47). Longhurst and his allies presented a report of their initial findings to President Hinckley with considerable trepidation, since the price-tag was an estimated $5 million. To Longhurst’s delight, Hinckley told them to keep on with the research. After trips to California to test organs in large auditoriums, Longhurst was thrilled with consultant Jack Bethard’s assertion that “a pipe organ will work in the auditorium as presently designed, without compromise to itself or to other architectural or performance elements.” Bethard further asserted, without qualification, “A pipe organ should be [the] musical backbone of the new assembly building” (52). Bethard’s conclusion and estimated cost of $3.5 million went to the First Presidency and, after “several suspenseful and prayer-filled days,” was approved (53). The catch was that the Tabernacle Choir was asked to contribute “about a million and a half dollars out of their private funds,” President Hinckley announced on July 24, 1997, and, with characteristic tongue in cheek, added that the choir would have “to not travel so much, to stay home and make that money available to us for this great building” (54).

In the remaining chapters Longhurst discusses the nuts and bolts of the organ’s design and construction. Meeting with potential builders, traveling the country to hear different types of organs, designing its façade, or face design, and “refining the stoplist” kept the planners and builders busy. The stoplist, Longhurst explains for outsiders, is like the “window sticker” for a new organ, identifying the “various sets of pipes . . . couples and accessories,” and other elements (81). Longhurst includes the actual stoplist in the main text in addition to an appendix of the pipe specifications. (Other appendices include a map of the console with its buttons and pedals, a timeline of the construction, an article on the Conference Center project from The American Organist, a record of project worker graffiti found inside the organ case, and a glossary of organ terms). Longhurst describes the console of the organ as being similar to the “cockpit of an airplane,” from where the “organist operates the instrument’s various controls and plays the keys, which finally enables the organ to make music” (99). His description conceives of the organ as an organic whole rather than a separated console and set of pipes. I imagine the console itself as the mere passenger seat on the body of the instrument, the organist as a person riding the back of a great whale.

Color drawings and photographs of the console give the reader a sense of intimate connection to the organ. Longhurst’s detailed story includes changes made to the console from its original plan and the considerations that made the changes necessary. They included jettisoning the “Stand By” and “On Air” lights which had been incorporated into the Tabernacle organ’s console “as a carryover from the early days of radio broadcasting” (109).

Chapter 9 describes the four-plus-year setup of the organ as the Conference Center was built around it. Employees of Schoenstein, the organ maker contracted to build the organ, spent “well over” an estimated 6,000 man-hours completing the project, which Longhurst describes with a true insider’s detail (141). The organ was not completed in time for the first General Conference held in the Conference Center in April 2000. Instead, an electric organ “performed competently, and the newly completed pipe façade added visual luster to its sound” (119). For President Hinckley’s ninetieth birthday celebration in June the Temple Square audio technicians piped in the organ from the Tabernacle, “I happened to be at the console and was most comfortable performing in my shirtsleeves, the only person in the dimly lit Tabernacle” Longhurst recalls (122). The workers were thrilled when the organ played for the October 2000 General Conference, as non-Mormon organ consultant Jack Bethards wrote: “we can only conclude that the Conference Center in all regards is nothing short of a miracle!” (128). Even then, the work was not complete, the voice of the organ required much fine-tuning to keep it up to Longhurst’s meticulous standards. It was difficult to find time to tune while tourists poured past and finishing touches were put in place in the Conference Center. Adjustments for temperature and humidity, an unpleasant odor in the blower room, and other considerations remained.

In Chapter 10 Longhurst explores the variety of pipes, the intricate wind system pumping air through the instrument, and the overall “action” of the organ, “the entire chain of events that must occur between the pressing of a key and the resultant sound from the pipes” (153). Photographs of the many pipes give readers a backstage tour. Finally, with precision perhaps only an organist can appreciate, Longhurst compares the Conference Center organ with the Tabernacle organ, claiming that “asking which organ we prefer is like asking a parent to name a favorite child” (158). He admits that the room in which the organ is held is a key determinant, and so the Tabernacle organ is better suited for recitals and concerts, although “we are always happy for another opportunity to play the Schoenstein organ” (158).

After being educated about the logistics of such an instrument, readers will never look at the organ in the same way again. Longhurst, who received Bachelor and Master of Music degrees from the University of Utah and his Doctor of Musical Arts degree from the Eastman School of Music, includes enough of the technical, but also the trivial: the pipes hidden behind the façade, the dummy pipes on the front of the façade to create symmetry, and the affectionate graffiti written inside the organ case (“[we] built this organ for the future enjoyment of our families,” and “Let’s go home”). Listeners will never hear the organ the same way again either, after experiencing the guided “tonal tour” of the organ, presented by organists John Longhurst, Clay Christiansen, and Andrew Unsworth on a CD-ROM included inside the back cover of the book. The CD demonstrates the different tones and sounds the organ can produce and includes recital pieces written by Bach, Mendelssohn, and others. A color wheel appendix can be used with the CD to identify the intended sound of the organ, adjustable by the organists depending on the piece and performance. Magnum Opus is a true insider’s view of organ origins.

[google images has some really nice ones of the organ.]

BHODGES received his bachelors degree in Mass Communications with a minor in Religious Studies from the University of Utah. He currently serves as choir director for the Porter Lane Third Ward and sings with the Utah Symphony Chorus. He blogs at lifeongoldplates.com.

Author: John Longhurst

Publisher: Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Genre: Music Architecture

Year: 2009

Pages: 210

ISBN13: 978–1–60641–199–5

Binding: Hardcover

Price: $32.99

[This review from the Journal of Mormon History vol. 37 no. 1 (Winter 2011): 246-249.]

When Mormon Tabernacle organist John Longhurst saw architectural drawings for the newly proposed Conference Center of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 1996, he was impressed by its sheer enormousness. Naturally, what attracted his attention most was the absence of any sort of visible pipe organ in the original plans. “The rostrum’s rear wall was to be some sort of attractive curtain or grille to be designed later. They called it a ‘screen wall,’” Longhurst recalls (46). Since accompaniment would have to be amplified electronically anyway, given the size of the auditorium, an electronic organ made financial and logistical sense. Still, Longhurst couldn’t hide his disappointment. Admitting his “prejudice” for pipe organs over electric, Longhurst began investigating the possibility of including a pipe with encouragement from LDS Church Architect Leland Gray. The beautiful organ which now serves as the backdrop of the Conference Center rostrum is the result of nearly a decade of consultation, design, and construction previously unmatched in the world of organ making.

Longhurst, who retired as Tabernacle organist in 2007 after 30 years of service, has crafted a biography of the mammoth musical instrument. It contains the detailed analysis of an expert insider written in a style suitable for the interested novice. Recognizing that his readership (and listening audience!) will include many organ aficionados outside of the LDS Church, Longhurst begins the book with a brief description of the Church’s historical geography and structure to the present.

Chapter 2 situates Mormon music in the religious atmosphere of the nineteenth century. From Emma Smith’s 1835 hymnbook (23) to the Tabernacle Choir’s 2003 National Medal of Arts awarded by President George W. Bush (28), Longhurst sees music as a crucial element of Mormon worship, recreation, and public image, a heritage which justified the money, time, and effort it took to make the new organ possible.

Longhurst narrates a history of the organs at Temple Square, as well as some of the key figures in constructing the instruments, in Chapter 3. The story of Joseph Harris Ridges leads off with a harrowing tale of danger at sea. Ridges, a British convert, constructed his first church organ in Australia, an ambition he had formulated as a young boy in London (31).The Saints in Australia wished to make a gift of it to “the Church in Zion,” and presumably paid for its shipping to the Salt Lake Valley. One of the Saints accompanying the organ recorded a terrible storm at sea during which he prayed fervently for protection. The miraculous answer saved the passengers and the precious organ from certain shipwreck (32–33). This organ was set up in the “Old Tabernacle,” a large frame building which preceded the now-famous turtle shell-domed Tabernacle. Pieces of this original organ were incorporated into the (new) Tabernacle’s organ between 1865-1875 (15, 35-36), which was expanded again in 1885.

“Few organs, anywhere, are as well known and highly regarded,” writes Longhurst, listing its technical dimensions with the specificity of an expert lover of organs (36). He also describes the construction and make of organs at the Assembly Hall and the Joseph Smith Memorial Building, accompanied by color photographs. However, the Conference Center organ would surpass all of the others in terms of logistical difficulties and pioneering effort.

When President Gordon B. Hinckley announced plans to build a new and much larger meeting place for the Saints on April 7, 1996, Longhurst played the session’s postlude, his mind filled with the new organ: “I was trying to visualize in my mind a room the size he described. If general conference were to be held there, surely an organ would be needed, but what would that organ be? . . . How were the Tabernacle organists and the rest of the Choir staff to become involved in decisions regarding not only an organ, but configuration of the choir loft and other music-related issues?” (43).

Several days later he found himself looking at the organ-less plans for the new center and went to work to discover the feasibility of a pipe organ for such a large auditorium. “Certainly no organ builder would want to risk tarnishing his reputation by attempting to install an instrument in an impossible situation” (46). Here the reader is introduced to the consultants, considerations, and culture of the organ-building world with its architects, acousticians, and stage designers (47). Longhurst and his allies presented a report of their initial findings to President Hinckley with considerable trepidation, since the price-tag was an estimated $5 million. To Longhurst’s delight, Hinckley told them to keep on with the research. After trips to California to test organs in large auditoriums, Longhurst was thrilled with consultant Jack Bethard’s assertion that “a pipe organ will work in the auditorium as presently designed, without compromise to itself or to other architectural or performance elements.” Bethard further asserted, without qualification, “A pipe organ should be [the] musical backbone of the new assembly building” (52). Bethard’s conclusion and estimated cost of $3.5 million went to the First Presidency and, after “several suspenseful and prayer-filled days,” was approved (53). The catch was that the Tabernacle Choir was asked to contribute “about a million and a half dollars out of their private funds,” President Hinckley announced on July 24, 1997, and, with characteristic tongue in cheek, added that the choir would have “to not travel so much, to stay home and make that money available to us for this great building” (54).

In the remaining chapters Longhurst discusses the nuts and bolts of the organ’s design and construction. Meeting with potential builders, traveling the country to hear different types of organs, designing its façade, or face design, and “refining the stoplist” kept the planners and builders busy. The stoplist, Longhurst explains for outsiders, is like the “window sticker” for a new organ, identifying the “various sets of pipes . . . couples and accessories,” and other elements (81). Longhurst includes the actual stoplist in the main text in addition to an appendix of the pipe specifications. (Other appendices include a map of the console with its buttons and pedals, a timeline of the construction, an article on the Conference Center project from The American Organist, a record of project worker graffiti found inside the organ case, and a glossary of organ terms). Longhurst describes the console of the organ as being similar to the “cockpit of an airplane,” from where the “organist operates the instrument’s various controls and plays the keys, which finally enables the organ to make music” (99). His description conceives of the organ as an organic whole rather than a separated console and set of pipes. I imagine the console itself as the mere passenger seat on the body of the instrument, the organist as a person riding the back of a great whale.

Color drawings and photographs of the console give the reader a sense of intimate connection to the organ. Longhurst’s detailed story includes changes made to the console from its original plan and the considerations that made the changes necessary. They included jettisoning the “Stand By” and “On Air” lights which had been incorporated into the Tabernacle organ’s console “as a carryover from the early days of radio broadcasting” (109).

Chapter 9 describes the four-plus-year setup of the organ as the Conference Center was built around it. Employees of Schoenstein, the organ maker contracted to build the organ, spent “well over” an estimated 6,000 man-hours completing the project, which Longhurst describes with a true insider’s detail (141). The organ was not completed in time for the first General Conference held in the Conference Center in April 2000. Instead, an electric organ “performed competently, and the newly completed pipe façade added visual luster to its sound” (119). For President Hinckley’s ninetieth birthday celebration in June the Temple Square audio technicians piped in the organ from the Tabernacle, “I happened to be at the console and was most comfortable performing in my shirtsleeves, the only person in the dimly lit Tabernacle” Longhurst recalls (122). The workers were thrilled when the organ played for the October 2000 General Conference, as non-Mormon organ consultant Jack Bethards wrote: “we can only conclude that the Conference Center in all regards is nothing short of a miracle!” (128). Even then, the work was not complete, the voice of the organ required much fine-tuning to keep it up to Longhurst’s meticulous standards. It was difficult to find time to tune while tourists poured past and finishing touches were put in place in the Conference Center. Adjustments for temperature and humidity, an unpleasant odor in the blower room, and other considerations remained.

In Chapter 10 Longhurst explores the variety of pipes, the intricate wind system pumping air through the instrument, and the overall “action” of the organ, “the entire chain of events that must occur between the pressing of a key and the resultant sound from the pipes” (153). Photographs of the many pipes give readers a backstage tour. Finally, with precision perhaps only an organist can appreciate, Longhurst compares the Conference Center organ with the Tabernacle organ, claiming that “asking which organ we prefer is like asking a parent to name a favorite child” (158). He admits that the room in which the organ is held is a key determinant, and so the Tabernacle organ is better suited for recitals and concerts, although “we are always happy for another opportunity to play the Schoenstein organ” (158).

After being educated about the logistics of such an instrument, readers will never look at the organ in the same way again. Longhurst, who received Bachelor and Master of Music degrees from the University of Utah and his Doctor of Musical Arts degree from the Eastman School of Music, includes enough of the technical, but also the trivial: the pipes hidden behind the façade, the dummy pipes on the front of the façade to create symmetry, and the affectionate graffiti written inside the organ case (“[we] built this organ for the future enjoyment of our families,” and “Let’s go home”). Listeners will never hear the organ the same way again either, after experiencing the guided “tonal tour” of the organ, presented by organists John Longhurst, Clay Christiansen, and Andrew Unsworth on a CD-ROM included inside the back cover of the book. The CD demonstrates the different tones and sounds the organ can produce and includes recital pieces written by Bach, Mendelssohn, and others. A color wheel appendix can be used with the CD to identify the intended sound of the organ, adjustable by the organists depending on the piece and performance. Magnum Opus is a true insider’s view of organ origins.

[google images has some really nice ones of the organ.]

BHODGES received his bachelors degree in Mass Communications with a minor in Religious Studies from the University of Utah. He currently serves as choir director for the Porter Lane Third Ward and sings with the Utah Symphony Chorus. He blogs at lifeongoldplates.com.

3

Comments

3

Comments