Implicit Confidence in God: Part 1

On faith, works and healing* Brigham Young August 17, 1856 After explaining why he spent more time preaching improvement rather than praise, Brigham said his next comments would "allude" specifically to people "who profess to believe in a Supreme Being," as to whether or not they had "implicit confidence in God." He tied the question into the ideas of both faith and works:

How slow many of us are to believe the things of God, O how slow. How many men and women can I find here who place implicit confidence in their God? Perhaps you might wish an explanation with regard to the term I here make use of. I will acknowledge my inability to explain to the fullest extent what I regard as implicit confidence in our God; the reason of this is the ten thousand opinions that people have. If I were to urge that we ought to have implicit confidence in the power and willingness of our God to sustain us by doing everything for us, that would cut the thread of my own faith, it would run counter to many of my ideas in regard to the dealings of the Almighty with the human family. On the other hand, how much confidence shall I have in God? One says: “I have no confidence in Him any further than what I can see, hear, and understand. I have no confidence that wheat will grow here, unless I put it into the ground; or that I will have food to eat, unless I take the proper steps for raising it, or purchase it from those that have it.” Both of these points are true in part, but the minds of the people are more or less beclouded. To explain how much confidence we should have in God, were I using a term to suit myself, I should say implicit confidence. I have faith in my God, and that faith corresponds with the works I produce. I have no confidence in faith without works. Shall I explain this?While recognizing the inadequacy of a simple example,[1] Brigham related a concrete experience involving an "over-righteous" priesthood holder in Nauvoo:

A President of the Elders' Quorum, old father Baker[2], was called upon to visit a very sick woman, a sister in the Church; they sent for him to lay hands upon her. It was a very sickly time, and there was scarcely a person to attend upon the sick, for nearly all were afflicted. Father Baker was one of those tenacious, ignorant, self-willed, over-righteous Elders, and when he went into the house he inquired what the woman wanted. She told him that she wished him to lay hands upon her. Father Baker saw a teapot on the coals and supposed that there was tea in it and immediately turned upon his heels, saying, “God don't want me to lay hands on those who do not keep the Word of Wisdom,” and he went out. He did not know whether the pot contained catnip, pennyroyal, or some other mild herb and he did not wait for anyone to tell him. That class of people are ignorant and over-righteous, and they are not in the true line by any means.Evidently Brigham believed the pot should have contained catnip, pennyroyal, or some other type of herbal remedy[3] because he believed Saints ought to make an effort to become well if they had the means. He did not advocate seeking a miraculous healing in lieu of (or perhaps apart from) available medicine. This brought to mind a recent article regarding a family in Wisconsin:

Police are investigating an 11-year-old girl's death from an undiagnosed, treatable form of diabetes after her parents chose to pray for her rather than take her to a doctor. An autopsy showed Madeline Neumann died Sunday of diabetic ketoacidosis, a condition that left too little insulin in her body, Everest Metro Police Chief Dan Vergin said.[4]Compare this with Brigham's sermon:

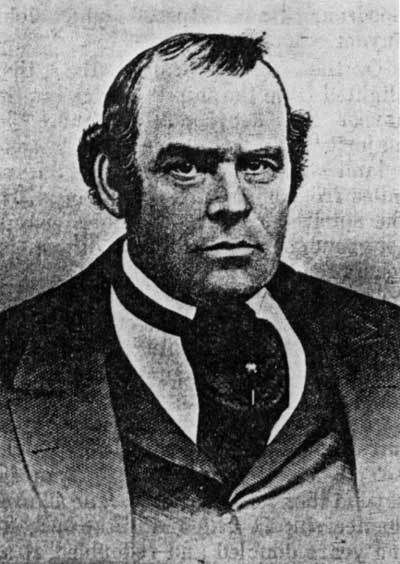

You may go to some people here and ask what ails them and they answer “I don't know, but we feel a dreadful distress in the stomach and in the back; we feel all out of order, and we wish you to lay hands upon us.” “Have you used any remedies?” “No. We wish the Elders to lay hands upon us, and we have faith that we shall be healed.” That is very inconsistent according to my faith. If we are sick, and ask the Lord to heal us, and to do all for us that is necessary to be done, according to my understanding of the Gospel of salvation, I might as well ask the Lord to cause my wheat and corn to grow without my plowing the ground and casting in the seed. It appears consistent to me to apply every remedy that comes within the range of my knowledge, and to ask my Father in heaven, in the name of Jesus Christ, to sanctify that application to the healing of my body; to another this may appear inconsistent. If a person afflicted with a cancer should come to me and ask me to heal him, I would rather go the graveyard and try to raise a dead person, comparatively speaking.Brigham added a caveat here which still emphasized the importance, or reality of prayer and miracles:

But supposing we were traveling in the mountains and all we had or could get, in the shape of nourishment was a little venison, and one or two were taken sick, without anything in the world in the shape of healing medicine within our reach, what should we do? According to my faith, ask the Lord Almighty to send an angel to heal the sick. This is our privilege, when so situated that we cannot get anything to help ourselves. Then the Lord and his servants can do all. But it is my duty to do, when I have it in my power. Many people are unwilling to do one thing for themselves, in case of sickness, but ask God to do it all (JD 4:24-25).In faith and works Brigham urged consistency, which is the subject of Part 2. *I've been troubled by this particular sermon for weeks because it is both expansive and remarkable; difficult to break into pieces to analyze without corrupting the whole or leaving something important out. (I have been attempting to make my posts smaller, as I feel the average blogger looks for a quick read.) I was half-tempted to just post the whole sermon and leave it be (you can read it here) but there is too much in it for me to not make some comments. So I'll make an effort to cover the rest of it over the next few posts in a series called "Implicit Confidence in God." Footnotes: [1] I do not think I can fully present the idea to your understanding, but I will a portion of it; and to do so, I will refer to a circumstance that transpired in Nauvoo (Brigham Young, JD 4:24). [2] Brigham may be referring to Jesse Baker, who served in the elders quorum presidency at Nauvoo (see D&C 124:137). Baker was born January 23, 1778 in Charlestown, Washington County, Rhode Island. "In search of adventure and fortune" Baker moved to Hoosick, New York. Working as a shoemaker and Thomsonian doctor (focusing on healing by use of herbs) he later moved to Ohio in 1835 at the age of fifty seven. Two years later Baker joined the Church and was ordained an elder. He was a charter member of and owned stock in the Kirtland Safety Society, a member of the Kirtland Camp who left Ohio in 1838, and was expelled from Missouri with the Saints in 1838-39. Baker was appointed by revelation January 19, 1841 to be counselor to John A. Hicks in elders quorum in Nauvoo. He received his endowment on December 15, 1845 and died November 1, 1846, at Mills County, Iowa. Perhaps Baker's previous experience as using herbs in healing led him to hold a strict view on the Word of Wisdom. See "Baker, Jesse," Biographical Index, BYU Studies, accessed 5-6-2008; Susan Easton Black, "Jesse Baker," Who's Who in the Doctrine and Covenants. [3] Catnip and pennyroyal are herbal remedies. For more on herbal remedies and Mormonism see N. Lee Smith, "Herbal Remedies: God's Medicine," Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 12:3 (Autumn 1979): 40. "Medicine and the Mormons: a Historical Perspective," Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 12:3 (Autumn 1979): 18–20. [4] Associated Press, "Girl's death probed after parents rely on prayer" MSNBC.com, accessed 5-6-2008.

1 Comments

1 Comments